The results of the 2024 monitoring surveys show that, after suffering large declines across the county, the number of breeding curlews has increased.

This result is in stark contrast to ongoing declines recorded across Scotland.

In 2024, curlew numbers in 100 of Orkney’s Local Nature Conservation Sites were surveyed for the first time in more than five years and curlew population trends are on the up.

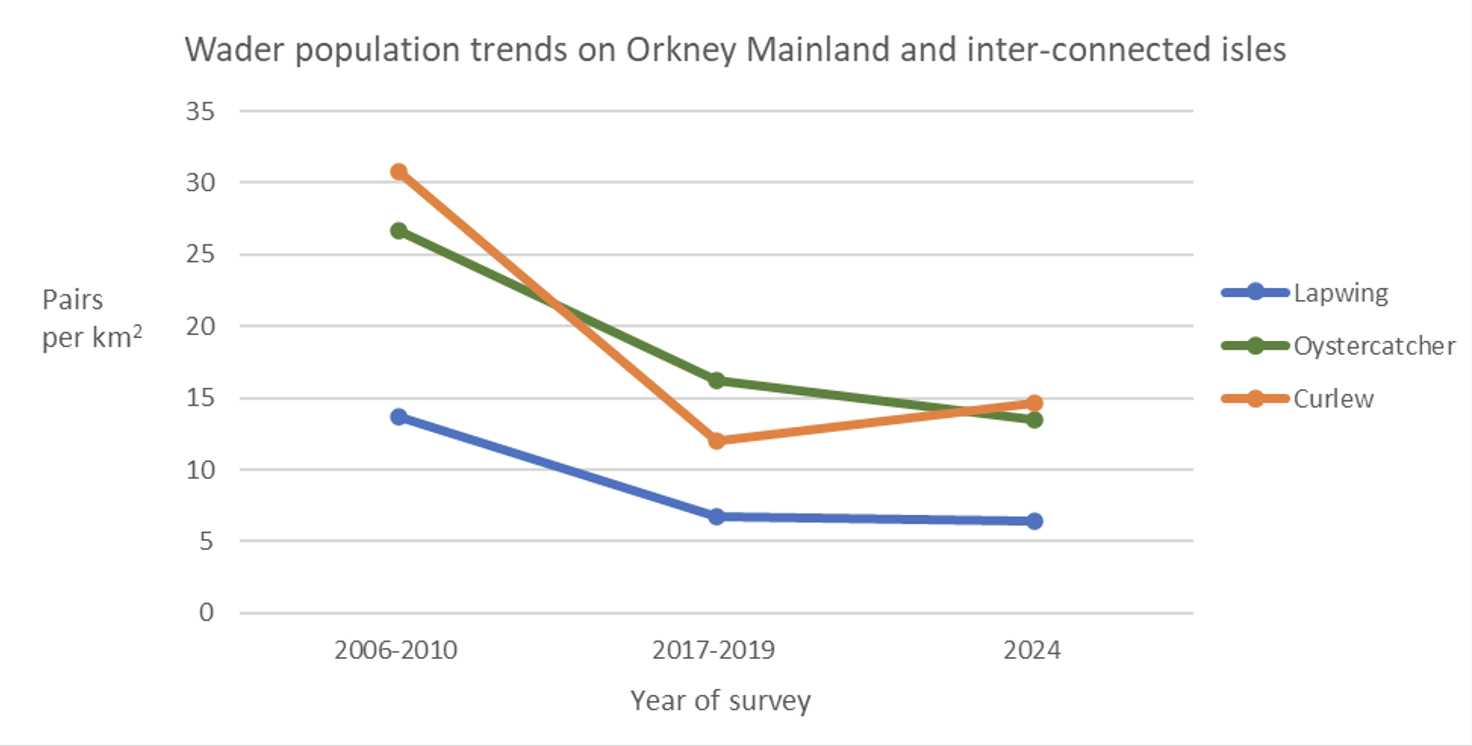

Between the original surveys which took place in 2006-2010 – the year stoats were first reported – and the surveys in 2017-2019 the number of curlews declined from approximately 30 pairs per km2 to 12 pairs per km2 across the Mainland and interconnected isles. The 2024 data shows a modest recovery from this low in 2019 – the year the ONWP began removing stoats – to 14.5 pairs per km2.

That’s a 21% increase in the density of curlews in Mainland Orkney and the connected isles, against a backdrop of 13% declines across Scotland.

Lots of factors influence population trends in wading birds like curlews including weather, but there are encouraging signs that the project’s efforts to remove stoats from Orkney are helping these vulnerable birds.

This positive population trend is an additional sign that fortunes may be changing for Orkney’s curlews after the dramatic increases in nest success rates (eggs hatching) since 2019 that were seen in the monitoring data from previous years continued in 2024.

The 2023 monitoring report showed nest success rates for curlews and oystercatchers were more than three times higher than when the project began in 2019, and, in 2024, nest success rates for curlews and lapwings reached record highs (82% and 51% respectively). Ongoing high nest success would help make these species more resilient to all the other factors affecting them for example poor chick survival due to bad weather as was seen last year due to widespread cold and wet conditions.